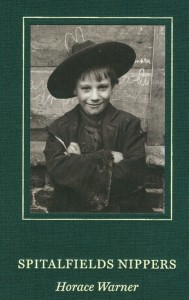

I’ve been researching much archival material on animals, including cats, in the 1800s, particularly in London. After a good zoom conference I became far more interested in the specific streets in which both working class people lived, but were also often the nearby places where cat skinners undertook nightly slaughter. As a Londoner I became even more engaged with the C19th street names since I knew those places still existed nearly 200 years on. I’d often walked near them but clearly hadn’t thought about those particular pasts.

Gravel Lane in Southwark where hundreds of corpses were held by a cat-skinner , who was then imprisoned. Now called Great Sutton St but the Gravel Lane is still noted in the sign …

Apart from the streets I have found many references to not only those who attempted to rescue cats and hold and obstruct skinners but also gave witness statements in courts. Court statements were not primarily undertaken by charity officers, employed for example by the RSPCA ,but by working class people, usually undertaking ordinary jobs, such as butcher’s porter, a wood chopper and a fringe weaver or they were teenagers watching local cats – and their attackers.People often found not just the cat corpses with their skins removed but helped demonstrate and organise against the skinners. Yet such accounts of working class people’s action seem to have rarely appeared in Marxist and socialist or social histories of earlier times. For example, while A.L. Morton’s work such as A People’s History of England , was well known explaining that “it was in London… that the new movement had its centre and main support” the nature of various action in local streets and feline – human relationships seemed not to have been recognised.Yet such past political action surely still needs to be recorded now…

My short article Voices for the Voiceless, has recently appeared not in an academic journal but in a popular magazine The Cat, now organized by the Cats Protection League. Hope you, like me, are a member and able to read it !

This year’s Durham miners gala displayed many banners.Free from the rain of 2024 many were shown in different ways. While the Chopwell had been presented many times before recently it was now just led by children wearing their own T shirts depicting the clear politics!

Elsewhere , with a wording ironically relevant to current political times was the Seaham Lodge. It presented the former coalfield but alongside the appropriate wording. That is the past should not be ‘forgotten’ particularly when radical politics are hardly part of ‘history’ nowadays.

Arising from the last gala I previously mentioned the visual image of Flack, the last pit pony to work in a British coal mine, ‘retired’, like other animals in 1994, & displayed in a poster. But now clearly presented on a Bearpark lodge banner was an image of a former horse alongside the men who also worked there. While such a situation was very difficult for horses in the pits, it seems here the joint animal – human activity was being clearly remembered – and now historically displayed.

The miners’ approach to positively remembering earlier times has not been widespread.In the recent Royal Academy Summer exhibition, artists Zatorski & Zatorski explained ‘ we are exhibiting the artwork “1” (comprising 101 rats) we are creating a limited edition “The One”’. These were presented as “White rat pelt, lined with 24 ct gold”. As one website noted “It instantly made me think about animal testing, and about the extremes people will go to, for riches…” The artists achieved much publicity and these dead animals were apparently giving the artists £85,000. Seems somewhat different to visually remembering men of earlier times trying to support horses …

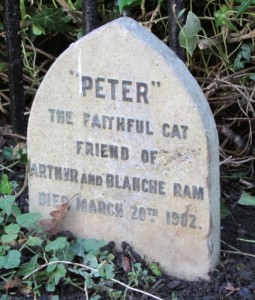

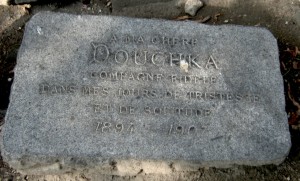

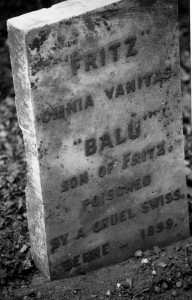

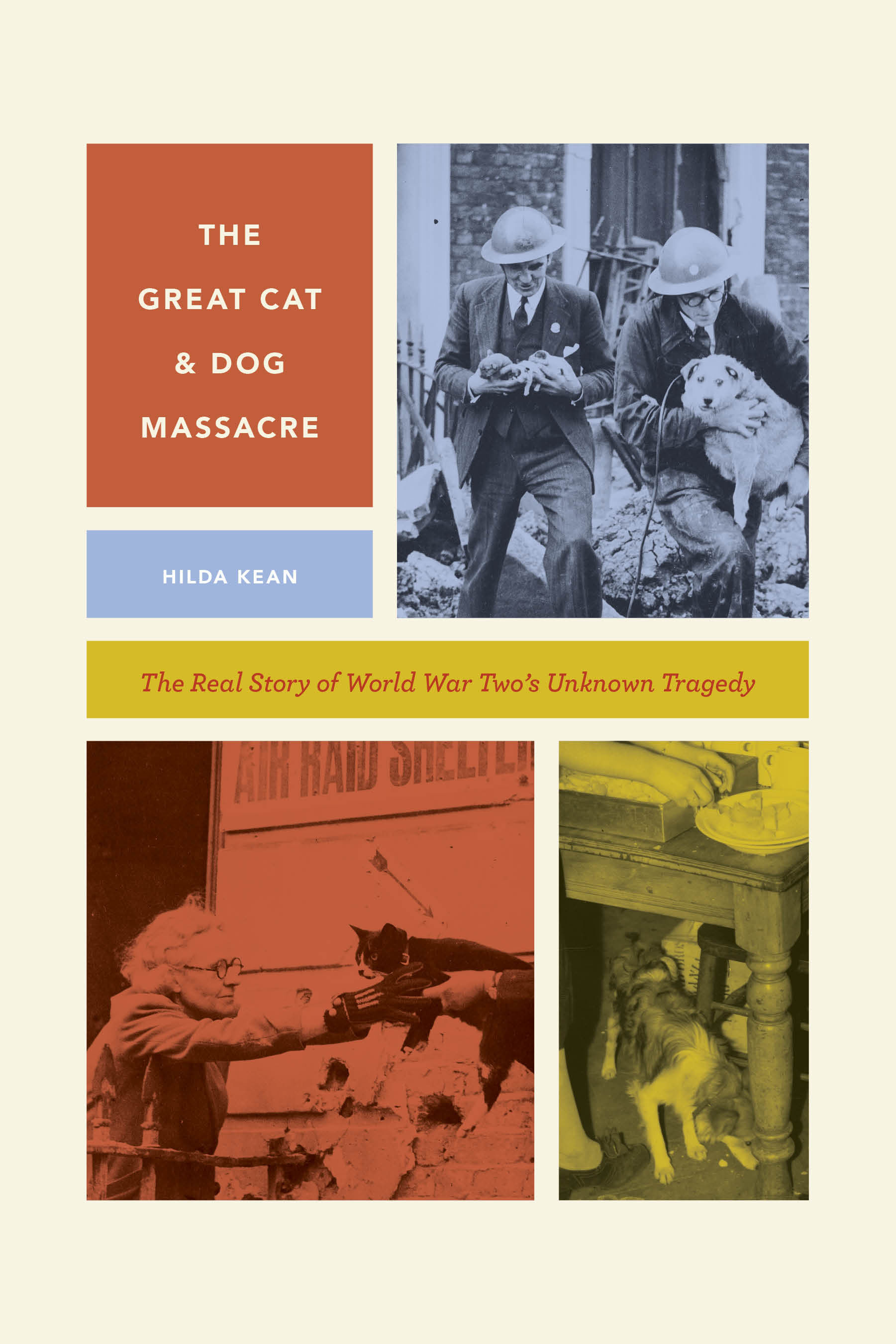

I am giving a talk this month on Saturday June 28th 2025 at 2pm at the Hastings & St Leonard’s museum. This year we’ve nationally been commemorating people who died in the war 80 years ago but where – and how – is the other past history of cats and dogs (and budgies) known? At the start of the war in September 1939 there was no Nazi bombing, yet in those first days many thousands of dogs and cats, particularly living in London, were killed by their owners. Although many domestic animals survived and have been remembered by many families, where is this part of a former past history known nationally? And where are local and national monuments to these pet animals erected today?

This is organised by The Hastings & St Leonards Museum Association, probably the oldest such Museum Friends group in the country, formed in 1889. Since 1905 it has raised funds to support the Museum & Art Gallery as well as being represented on Hastings Borough Council’s Museum Committee which advises the Cabinet on all matters related to the Museum & Art Gallery. There is a cost of £5 – not for me as a speaker -but to go towards our funds to help the museum continue to operate in these financially dire times.

The meeting is near Hastings station at Durbar Hall – ground floor – in Hastings Museum and Art Gallery in John’s Place on Bohemia Road TN34 1ET.

Recent London exhibitions have displayed past images of many art works which have not necessarily been previously exhibited there. In the last few months animals in paintings, sketches or sculptures were often presented.

Many of the images in the National Gallery’s display from March until late June displayed works from Siena in the 1300s. Much representation was of religious material but items which do present animals or perhaps I’m just searching for them. Looking at an manuscript item of Equity and felony, leaf from Laurent d’Orleans, La Somme le foi c.1290 – 5 appeared an aspect of Noah’s ark from Genesis in the Old Testament.Here stood a cat alongside animals not necessarily seeing just humans but animals from other groups.

This was not unique since a rug, attributed to Turkey, was also hung again showing a cat, as well as sculptures presenting lions under Mary’s chair by Giovanni di Agostino The virgin and child with Saints Catherine and John the Baptist c.1340 -50.

But there are other images of animals outside certain buildings – if we are looking for them.For instance in a side turning, off Leicester Square, is a listed building, The Church of Notre Dame de France,(a Roman Catholic church) previously extant since the late C18th but rebuilt by architect Hector O.Corfiato in the 1950s. Inside are frescoes by Jean Cocteau, but outside on two pillars is a series of eight scenes from the life of Mary, carved by students from the École des Beaux-Arts – accompanied by various animals .

Over this weekend “ lest we forgot” in town and villages many people have been remembered. Marches and wreathes, publicly or as an individual cross recalling aspects of a person’s life in war. Yet many animal wreathes were also given in Park Lane.

On Friday 8th November the Animals in War remembrance gathering took place at the animals memorial in London’s Park Lane. Various short speeches were given by the Household Cavalry and Mounted Regiment, Welsh Pony & Cob Society,Zoological Society of London, and Provost Marshals Dog Inspector of the RAF Police. I gave a short piece still remembering animals from the Second World War.

As I have written elsewhere 26% of London animals were killed in September 1939 killed before any bomb was dropped here. Fortunately the majority of the population were nor involved in this destruction of 400,000 cats and dogs – but a minority of individual people were. The stories of those times were often discussed and still remembered in families over decades.

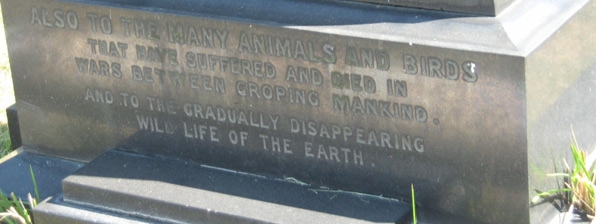

The animals on war memorial sculpted by David Backhouse and displayed since 2004 is not unique. In Dartmouth Park in Morley in Leeds exists the Stone of Remembrance sculpted by Melanie Wilks and erected in 2011. However apparently only two such memorials commemorating many types of animals dying in war in many ways.

This is part of our past history for generations to come.While it is positive that those times are remembered , we should surely commemorate such issues publicly?

.

Even in the rain in July 2024 the Durham miners’ gala was not just remembering the miners’ strike of 40 years in 1984-5 but, presenting a militant trade union platform and showing very many banners. This was the 138th Durham miners’ gala. The County Hotel balcony at which former important labour members had been seated, watching the banners go by, had included Nye Bevan, Michael Foot,Tony Benn, Denis Skinner, Harold Wilson (!) and many others as the programme noted. Unsurprisingly Keir Starmer was not present here, but sitting on the platform and being welcomed by the wet banner holders was – Jeremy Corbyn.

Held here, but very wet indeed , was the Follonsby banner (hence a clear image from a book) made for The Follonsby Lodge of the Durham Miners Association in Wardley, Gateshead. The banner was one of just three in the entire British coalfield to feature communist leader Lenin and the only one to also include the Irish revolutionary James Connolly, executed after the Easter Rising in Ireland in 1916. The other figures that featured on the banner were Keir Hardie, former Scottish miner and founder member of the Independent Labour Party in 1923, AJ Cook miners’ leader in the 1920s, and Follonsby Lodge Secretary George Harvey, a Ruskin student 1907-8. It was reproduced by Lewis Mates, Davie Hopper,David Douglass, and others. David was a third generation Follonsby miner, then active in Hatfield in Yorkshire during the 84-5 strike and also a former student at Ruskin College, under Raphael Samuel, and a subsequent historian and writer.

Decades ago John Gorman wrote the excellent book Banner Bright discussing many important trade union banners, but many had disappeared even years before. He explained that in 1935 the NUM Chopwell lodge banner was painted again with Marx, Lenin and Keir Hardie replacing a badly torn one, with Walt Whitman’s clear phrase. ” We take up the task eternal, The burden and lesson, Pioneers! Oh! Pioneers” In the recent 2024 Durham miner’s gala it was still there, albeit covered to prevent the bad rain, (hence an earlier photo).

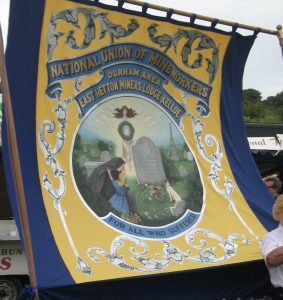

This year covered to keep dry was the East Hetton Lodge showing a grave commemorating “all the miners killed and injured “ with the dates seemingly now reworded 1839 -1983 with a grieving dog nearby.This image was not unique to the NUM but others unions such as the TGWU displayed graves with dogs on what John Gorman explained as “coffin clubs”. Here a dog sees the grave where miners have been remembered.

Also present, protected behind a fence, was the Morrison Lodges banner commissioned in 2018 to commemorate the Morrison (and Morrison Busty) pits both closed in 1964 and 1972. Apparently the image of a lion, lamb and child is based on a biblical scene though seemingly different to many Renaissance images presenting religious scenes with animals.The message Reign of Peace, quotes the bible for the millennial period where apparently animals would exist alongside humans but the individual lion seems more important on the banner!

Not on an extant banner but still portrayed on a poster, often for purchase at the gala, was Flack , the last pit pony to work in a British coal mine, brought to the surface for the last time in 1994. Alongside other ponies from Ellington Colliery in Northumberland, he too retired.

Despite the heavy rain- and the dubious political scenario arising from July 4th- here it was positive to certainly remember earlier times in many important ways. Think now about going next year!

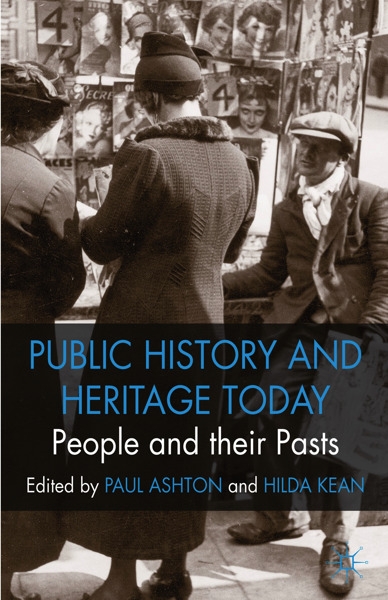

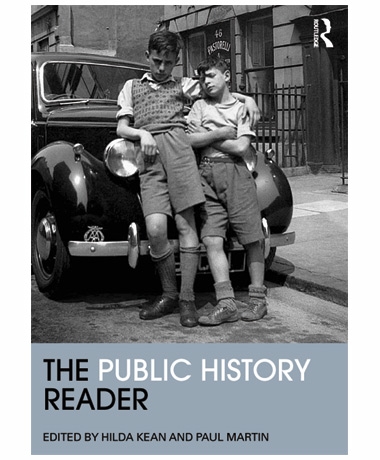

Since the 1992 Prof Paul Ashton has been the main initiator and editor of the Public History Review in Sydney, Australia. In those 32 years he has published many of these journals. But, as Paul has just recently explained, “I must report with some regret, its final year of publication”. As he reminds us, over 300 articles as well as many more reviews and reports from the field were published. Focusing on public historians, it has 2,814 readers in over 50 countries; 366 registered reviewers; and averages around 2,500 abstract views per month. But, as Paul Ashton has explained, the Public History Review is now closing and archived and available through the ePress. Like many other public historians, from all parts of the world, I have previously attended and spoken at the local conferences and then published outcomes in the journal, which included several statues and memorials which have been part of attention to public history not only in Australia but certainly Britain, as was the attention to women’s suffrage historically in the different places.I am pleased that his historical energy was also asserted in our jointly edited book Public History and Heritage Today. People and their Pasts (Palgrave 2012) arising from our international conference at the former Ruskin College, Oxford.

It’s positive that, having retired from UTS , Paul Ashton is now writing further books, now aimed at school students as, “they allow for students to understand how history is not just something that can be found in textbooks, but rather that it is something being made around them, and that they are creating their own histories every day.” His new four books are presented under the engaging title ‘Accidental Histories – exploring the role of accident and serendipity, to make history.’One of the books, Yarri , is set in Gundagai, June 1852 where ‘Yarri and Jackey Jackey sat in the hollowed-out trunk of a huge, old gum tree on the top of Mount Parnassus. They looked down to Gundagai through the heavy rain. The river had swollen and the town was in trouble. But what could they do?’

As noted in the image above it was only in 1990, 150 years on, that a new monument was erected in North Gundagai cemetery since this had been ‘in the memory of Gundagai people for generations’ when the 2 aboriginals , Yarri and Jackey Jackey had rescued 49 people from the swollen river.This recent memory has now become an aspect of wider past history.

Public history has not just increased over decades years but as noted above , with increasing influence in heritage and memorialisation and, of course, with information past on to the younger generation – thanks to historians like Paul Ashton!

Robert Gildea had been active as a professor of modern history in Oxford for many years often mentioning oral history when he spoke at our regular Saturday public history seminar at Ruskin College.Yet by 2023 his important new book arose called,The Backbone of the Nation: Mining Communities and the Great Strike of 1984 -5. And now in paperback. This includes many oral testimonies from miners and their families of those times – and well worth reading!Clearly the BBC must have positively engaged with this book and invited him to be the historian working with determination in the recent BBC1 programme Miners’ Strike: A Frontline Story. Here the story of fifteen men and women, including some oral accounts, returned older people (and younger people not alive then) to the years of 1984-5. If you missed the programme , do watch it!

However, Gildea’s latest book has just been published in 2024. It’s called What is History For? As he argues in the preface, although historians routinely think,“what is history?” but about what it is for, much less so. This suggests, he states, that history is not simply an academic subject,“ to be studied for its own sake.” Much of his discussion and emphasis records the way in which a history of the past has been re-written in other ways at different times.He carefully suggests that historians may sit in university libraries away from the cut and thrust of power, “but rarely do they escape the power implications of their work.” Yet in history-writing in other ways, new groups, who have been excluded from past histories such as workers or women or black minorities, have been reclaiming another past history.His is a strong argument, touching on a large range of former histories, as developed through the book. He concludes that “not everyone is able to write a memoir of such subtlety and scale about a generation.”Instead, he suggests public history which “holds that anyone and everyone can write a life story or fragment of it” is based “on the idea that all people are active agents in the creation of history”. As he concludes he suggests, “everyone is a historian.”

Do read this book’s viewpoint.It helps recognise the range of questions and personal answers we might use nowadays whether family histories, local histories, new plaques, attention to heritage, oral stories, past union and political campaigns and perhaps also note the role of public history in facilitating this stance…

A refurbished Tunbridge Wells Museum includes particular women – and supports certain animals

Going to a newly changed museum isn’t always positive, even if objects are revised or created in other ways. However, the central museum in Tunbridge Wells has been revamped in many engaging ways. Thus the museum’s new title, Amelia Scott, has given attention to Amelia Scott, who has recently been described in the Oxford DNB by Anne Logan as “social reformer & women’s suffrage campaigner”. She had been a local vice president of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, and a supporter of the Women’s Suffrage Pilgrimage through local towns to London in 1913, as recorded in the museum’s photos.

As a councillor she explored the poor law, the development of a mortuary, in addition to the welfare of women and a soup kitchen for the unemployed.

However, in addition to a few artefacts presenting Amelia there is another fascinating item. This was a sheet from a diary written by Olive Grace Walton, a local activist in the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) while she was imprisoned in various prisons before the 1914 war. As shown in a suffrage book of 1913 she recorded that “Mrs Pankhurst’s trial has been put off until next week. 100 witnesses to be called”. Although Olive is not yet covered in the DNB she had previously been both on hunger strike and repressed with forcible feeding in April and June 1912 when locked up in Aylesbury prison.Let’s hope this information can also be included.

Upstairs , good arguments have even been presented towards many previously killed and displayed birds and animals which have been shown here since it opened in 1885 in earlier ways. Displays now attending the taxidermy collection “streamline”, prioritising local links.As the historical staff recognise, their broad exploration of modern conservation and natural history must survive. As earlier reported ,the newly interested heritage, culture and learning hub suggested “it will be rich with objects and will offer and imaginative programme to engage and inspire visitors.” Already this seems on track!

However, the extant nearby plinth to Air Chief Marshal Hugh, Caswall Tremenheere Dowding, recognises he was particularly decisive in aspects of the Second World War, but ignores his later supportive position on animals. Dowding used his later position in the House of Lords to speak against animal experimentation and the cruel ways in which animals were poisoned in the wild; indeed most of his speeches in the Lords were on animal welfare. After his death in 1970 the Lord Dowding Fund for Humane Research, to promote practical alternatives to animal experiments, was established in his name by the National Anti-Vivisection Society. He had lived, with his wife Muriel, in Calverley Park,Tunbridge Wells. Perhaps the new museum with its interesting engagement with people – and former animals – might also acknowledge the local resident’s own performance to support them?

In Old Amersham, Buckinghamshire, inside -and near – St Mary’s grade 1 listed church are rather unusual images. Since the C13th the Church of England existed here in different ways. But on a hill overlooking the church I recently discovered a memorial to the Amersham Martyrs, who were Lollards. Six men and one woman had been burnt at the stake nearby in the early 1500s. As followers of John Wycliffe they had campaigned for the Bible to be translated into English and read. Their memorial now stands but it was not even erected until 1931 by the Protestant Alliance.

Rather different stone images have also been displayed in the local St Mary’s Church. In the south porch not humans but animals are presented. Placed here in the fifteenth century were two sculptural carvings, of a dog and a pig, which still exist. They were apparently forbidden from entering the church (!) though no stories seem to have been displayed about their construction, sculpture or comments of the time.

If anyone knows more about the pig and dog church issues do let me know!

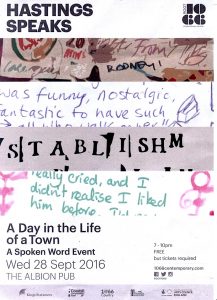

At the end of Robert Tressell’s The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists the radical outsider, Barrington, is being transported in a train away from Owen, and his son Frankie, who were living in Milward Road in Hastings. From the window,“the train emerged into view, gathering speed as it came along the short stretch of straight way… they saw someone looking out of a carriage window waving a handkerchief, and they knew it was Barrington as they waved theirs in return…”

Now displayed on a house in Milward Road is a large plaque. The house is adjacent to the twitter steps (often occurring in Hastings up the steep hills ) and named Noonan’s steps (after Ron Noonan, the man and writer, often published as Robert Tressell).

The plaque, accurately dated as 2 June 1962, has been well recorded by the local writer F.C.Ball in his book, One of the Damned, published in 1973. As Ball clearly explained, in that year, the “TUC Annual Congress of Trades Councils in Hastings” took place.This included the ceremony for the plaque in Milward Road. It was placed there by the Hastings trades council and unveiled by Cller F.Watts, secretary of the Essex Federation of Trades Councils.

In years to come, in 1999, the first weekend event took place of the Robert Tressell festival. Another plaque to Tressell was then unveiled, outside a different place, by Michael Foster MP. He was the first Labour MP in the area from 1997 – 2010. (His presence is still unique as the only Labour MP in this now Conservative parliamentary town). When Foster won the new seat his words were drawn from Tressell, and then recorded in the Hastings Observer with his words , “Mugsborough finally has its first Labour M P.”

Recently, in St Leonards, a community arts groups explored “Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands,” including an arts exhibition artist Dr Jude Montague. She wrote, “I contributed from my own workshop on King’s Road with an exhibition that looked at the news reportage reaching the British Isles from Crimea in the 1850s, focusing on Roger Fenton’s famous war photograph, “The Valley of the Shadow of Death.” Thus she reproduced this as a “cyanotype” and exhibited it, with multiple layers, in a compound wall.She also played a version of the reading of Tennyson’s poem on The Charge of the Light Brigade, which invited people to meditate upon its landscape.But also displayed was a photocopy of Sandy, a dog from the Crimea, displayed in the Illustrated London News of 23 February 1856, in which I was interested, as he was different to the other Crimean animal images I knew.

Sandy was then 7 years old who had travelled with the Lieutenant Lempriere in various countries, being described as a water dog. When his owner returned home to Britain, in poor health, Sandy also returned to Brompton Barracks, in Chatham, where he was presented with a medal. As the ILN article explains “The medal is not a real Crimean one, as dogs are not so decorated, however distinguished in the service.”

However, he was not the only Crimean animal recognised in England.In the winter of 1855 – 56 the painter John Dalbiac Luard had previously visited the Crimea, where his brother, Captain Richard Amherst Luard of the 77th (The East Middlesex) Regiment of Foot, was on active service. Dalbiac Luard’s oil painting, A Welcome Arrival, on display in the National Army Museum – https://collection.nam.ac.uk/detail.php?acc=1958-08-18-1z

presents three officers in a rough bivouac. Behind them, fixed to the wall, are dozens of images. including those from the Illustrated London News including animals. But placed among the three men is a small table on which sat a tabby cat with a white chest. The presence of the cat seemed to signify that the bivouac had almost become a home.

The cat, then called Crimean Tom, was around eight years old and had been found in the city of Sevastopol after a year-long siege. He was understood to have led the British soldiers to a storeroom of Russian supplies, thereby helping to save the British and French soldiers from starvation. He was subsequently rescued from the city and duly brought to England by the officer William Gair. He died in London in 1856. According to the museum, albeit somewhat sceptically, Tom has now been preserved as a taxidermic figure. However , he did come after the Crimean war directly to the museum; rather, he was bought from Portobello Road market in the 1950s, by Lady Compton Mackenzie, who donated him to the museum.

At least such animal-human stories are now being publicly shown from much earlier times. Yet the researching and hosting of many animals, particularly ginger cats , from earthquakes and bombing in Syria , seems rarely displayed. However the sanctuary is online with great photographs in Ernesto’s Sanctuary for Cats in Syria. https://ernestosanctuary.org/

Sadly, Emeritus Professor Jorma Kalela , who was born in Finland in 1940, died late last year in Helsinki when he was 81 years old. Although I knew and personally talked much to him about history over several decades I do think his past experience should be more remembered , particularly amongst many types of historians. He had studied political history in Helsinki and had worked as a researcher for the Finnish Academy 1971-1977 and 1990-1992 . He subsequently became a Professor of Contemporary History for many years at the University of Turku. Apart from links with Swedish and German colleagues he also spent many times in Britain. He was also a senior member of St. Anthony’s College, Oxford and a visiting professor at the Institute of Historical Research at the University of London.

Meetings took place in London and elsewhere. He would often stay in a friend’s house protecting her cat while she was away. We often emailed each other. As he wrote back to me about The great cat and dog massacre book, saying “Don’t remember any more how many years ago it was that I heard of your project for the first time!” He was often here to talk about public histories, and his discussion with Toby Butler on oral history. His English book, Making History. The historian and Uses of the Past came out in 2012 through Palgrave – and is still very worth reading. As he notes , from 1979 to 1986 he spent time in the Finnish paper and pulp industry, Paperilitto. This included more than 200 members of the union undertaking research including their own family histories. As he explained, through this engagement he also altered his personal understandings of the past particularly in politics. Kalela became clearly aware of the political position of his own grandfather Aimo Kaarlo Cajander, a former prime minister of Finland who died in January 1943.As he importantly argued in his Making History book “ History is an everyday matter, everyone really has a personal connection to the past, independent of historical enquiry.” His position has certainly influenced me when writing about various individuals’ views on local and family history in perspectives which have been rather different to those of academic historians.

Paul Martin and I were pleased that Jorma agreed to let us publish an extract of his past history in our Public History Reader (Routledge 2013). As Paul Martin explained, in our consideration of the ways in which the past had taken on a heightened popular sense of importance in the present ,clearly questions were being raised about “Who is Making History” – as Jorma was importantly exploring.He often attend conferences and seminars over here and I was pleased that he agreed to give a presentation at the ninth – and last – public history conference in 2009 at the now destroyed Ruskin College, in Walton Street ,Oxford. Entitled Legacies and Futures: The History Workshop and Radical Education it included Anna Davin of History Workshop Journal, Marj Mayo and Ken Jones. As Jorma explained, he was thinking about new visions and practical examples.

Jorma’s clear interest in historical approaches did survive in recent years. Responding to an email about my own accident he explained the changes he received through a stroke.He wrote “To survive mentally in the hospital I had to execute two promises from the pre-stroke-time. It meant one article on the ethics of historical research and another on the opposition of historians towards secondary reflection on their own practice…”

I hope those of us who knew him and his engaging historical work will also continue to positively remember him

.

Post lockdown art exhibitions at the Romney Marshes were recently able to be visited . Irrespective of the art displayed, aspects of the formal interiors including fonts, walls and particular biblical quotes always create interest – at least to me.

Aspects of the font in the church of St Augustine in Brookland, is fascinating. As Ann Roper has described, this was made by Norman or Flemish craftworkers of the C12.The signs of the zodiac, and months of the year, were explained.Clearly presented were animals such as a pig or horse or fish alongside humans.

It seemed to remind me of the figures of humans and animals I saw many years ago in the baptistery near the duomo in Parma in Italy’s Emilia Romagna . Those too were from the C12th – this time as small statues from the workshop of Antelami. Odd how different animal images bring back memories of decades ago…

Similarly the biblical quotes in St Thomas Becket, Fairfield, as described by David Cawley, still remain – and are included – in many Romney Marches churches.

As a child I was formally instructed in Non-Conformist religion (as other historians also state they experienced and later critically reported.) I now find these phrases unusual.

(As a teenager, often late to school I wrote biblical quotes from the Cruden’s Concordance on the class group’s door, which my grandfather had used for his street preaching against drink. Instead I briefly quoted “Woe to those who rise early”. Here I deleted the next phrase “ to tarry after strong drink” to instead emphasise lying in bed. However , the protestant school teacher scribbled in opposition different biblical quotes asserting the need for attendance …. )

But in recent months , despite online library work, I have yet to find the local explanations for these displays of specific quotes. I would welcome information on reading historical writing and sources about the reasons for their insertion .

Under Dr Alex Lockwood, through the funding of the Culture and Animals Foundation there are currently audio podcast talks from several animal historians on animal welfare changes over the last 200 years – and the need for far more protection of animals

I gave an audio response which was summarised as “ We spoke this summer about the development of human-animal relations in the 18th and 19th centuries, and the many acts of ordinary people against cruelty to animals, that were also taking place even as the great and good were bringing legislation in parliament.”

This is not quite what I was stressing in the podcast but rather the protection of DOMESTIC animals after the 1822 Act often led to new legal changes. This often occurred through working class or local residents protecting cats and dogs in courts. Often ordinary people would contact the police, or personally attempt to stop those killing animals; and then appearing in court, as witnesses against those cruel attackers. They would also demonstrate and protest against such hostility.

There seemed to have been neither BBC recognition of Martin’s Act in 1822 or even accounts in mainstream newspapers. It hardly implies that awareness of the need for more assistance to animals seems well known…

Access audio podcast here – https://soundcloud.com/chart2050/cats-dogs-other-people-hilda-kean-martins-act

An historical event occurred on 22 July 1822 when Royal assent was given to a new act, often called Martin’s Act, under the name of MP Richard Martin. 200 years ago, for the first time in this country, it became an offence for any persons to wantonly and cruelly “beat, abuse or ill-treat any horse, mare, gelding, mule, ass, ox, cow, heifer, steer, sheep or other cattle.” Interestingly the actual wording from the legal Royal minutes simply states “ An Act to prevent the cruel and improper treatment of Cattle”.

In some ways this sounds good but earlier attempts had failed and still continued for some years after 1822 including bull baiting and cock fighting. It was also then realised that ordinary cats and dogs were not included within the new law. Thomas Fowell Buxton MP -and RSPCA supporter – stated the Act “had put an end to half the cruelty which formerly prevailed in the country”. The word “half” was relevant since, as he knew,“the instances of cruelty to animals were numerous” and was aware of “the sufferings of dogs and cats”.

Throughout the following years many attempts were carried out in courts by local people as witnesses or demonstrators trying to protect animals, such as cats. Although laws to protect domestic animals such as dogs and cats and even monkeys were passed in 1835 local people’s defence of animals was clearly frequently undertaken – as abuse still occurred.

Nearly 200 years on, animal cruelty has still happened. We were reminded in June when West Ham footballer Zouma was violent towards his two cats and only received 180 hours of community service – and his brother Youan 140 hours. Zouma received just a fine of under £9,000 in court . Pointedly, he had had 250K already removed by his West Ham football club which clearly stated that “we condemn in the strongest terms any form of animal abuse or cruelty” and “not in line with the values of the football club”- and gave the £250k to animal charities. At the time a woman had rejected going on a date with Youan ,the instagram snapper of the two Bengali cats, because of the brutality visually seen.Thus the images had been forwarded and legal action taken.

The positions taken by the West Ham employer and a woman supporter of cats were not simply unique views of contemporary times. Rather, people’s own acts defending animals- even when statutory laws had been agreed – have regularly occurred in this country particularly after the Martin’s Act was passed.

As a way of remembering the positive acts taken by ordinary people, particularly Londoners,I have been talking to the UK Centre for Animal Law (A-LAW) about people defending ordinary animals in the nineteenth century. These also relate to their conference this week on Animalaw: Visioncomments of the future, The Martin’s Act Bicentenary Anniversary Conference 2022.The conference is talking about the need for legal changes nowadays to protect animals.

I have been recalling the past history of humans defending animals (as well as those attacking them) which can be heard from the audio podcast over many weeks. https://podcasts.apple.com/gb/podcast/talking-animal-law/id1578444621

Such acts to protect animals were not just something new under contemporary and even pandemic times. Rather, cruelty towards animals had continued for centuries – although some humans protected them even many years ago, We still need to be aware of past positive treatment towards animals – as well as continuing acts of cruelty.

Decades ago I had researched and had published a book I called Deeds not Words. The Lives of Suffragette Teachers, arising from my earlier PhD on history and education. Then I was a school teacher at Quintin Kynaston, a progressive London school, and active in the local Westminster NUT. To be honest I had never been that interested in the suffrage movement, apart from Sylvia Pankhurst, but suddenly came across the way many women teachers activists organised in the NUT to try and get the union’s support for the vote. On one occasion I saw that 70 branches had all passed the same worded motion for the NUT conference. We could never had managed to get more than about 10 branches supporting the same wording even in the 1980s! It was that which interested me. In due course the PhD was passed without amendments! But there was included a huge appendix of a biographical list of people I had researched in the NUT, NUWT, TLL . Even I realised that I would never have got a publisher interested in all of them but in future months with a focus on 4 women teachers ,namely, Theodora Bonwick, Agnes Dawson,Ethel Froud and Emily Phipps Pluto published.Later all four were included in the Oxford DNB which I had suggested along with many women who had protected animals such as Mary Tealby the founder of the Battersea Dogs’ Home.

I had noticed that in Swansea Emily Phipps had received a blue plaque; I had met a related relative of Ethel Froud in Australia involved in family history at a 2014 Conference;Sarah Bonwick, the mother of Theodora, had now been well analysed by Colin Cartwright in the Baptist Quarterly of 2021; and Agnes Dawson’s archival material had been deposited several years ago in the Bishopsgate Institute which I had positively seen but not returned to think about more.

Suddenly just weeks ago I was invited to see Agnes Dawson’s blue plaque in Newport, near Thaxted in Essex, and went.Some of the politics I had written about seemed to have been noted. But, far more importantly. also present was one of Agnes’s great nieces, Jill. Not only did she recall and remember her aunt but also knew about visiting her house, ‘The Hut’ and noting where the allotment was and being invited in by the new owners.

The personal position towards a dead, famous, relative was important and far more engaging with comments often made by academic historians. This open attention to Agnes’s clear emotional, as well as political ,work towards children was striking – and clearly relevant. I am reminded of earlier positive thinking in a public history perspective that is generally not quite as important nowadays as it was just some years ago. Ordinary and local people are far more important than simply historical researchers….

Cats – not simply adopted through Covid – living with people for over 8 years and to whom my last animal history was dedicated together with Sidney Trist …

In 2021, cruel maltreatment of cats during 2018 and 2019 was prosecuted. It had resulted in between sixteen and twenty three cats being killed or injured by one man – in Brighton. Successful action was not primarily taken by the local police. Rather, it was undertaken by local cat lovers, including a woman named Boudicca Rising, from a campaign group,who tried to catch a suspected killer. Further, a woman owner of a killed cat set up a CCTV system to capture on camera a fresh cat attack.And did this.

Thus Steve Bouquet, a security guard,was jailed for 5 years and 3 months in July 2021. The judge Jeremy Gold QC said, “It is important that everyone understands that cats are domestic pets but they are more than that. They are effectively family members…” These comments were not entirely different to words in the nineteenth century. A London alderman would state that a prisoner attacking cats “ deserved to be skinned alive for his barbarity” (1831) while radical activist Leigh Hunt described cats being liked and “the picture of comfort”(1834) in his London journal. Yet recently defined by BBC news and the press in January 2022, the cat killer died in Kent from thyroid cancer on January 6th.

Although the press generally covered protecting cats, there was no understanding that acts defending cats were not at all new! After Martin’s Act passed in July 1822, the first in this country to defend many animals, from the 1830s new laws to defend domestic animals emerged. The Pease’s Act of 1835 introduced laws to defend and protect cats and dogs, including dogs transporting animal food or cats killing rats in factories and homes – or both giving emotional support to people.

Court cases included police activity bringing men – and women – cat killers to magistrates’ court grew at that time. But – like now – it was primarily local people who took a stand. Obviously there were no cameras then but there were people who dragged killers to the police to arrest them, and then gave statements in court, ran demonstrations outside, and even physically threatened offenders.

This action to defend owned and stray cats and dogs was not new just to Brighton nor to the twenty first century but became part of animal protection by humans in this country nearly 200 years ago.

As I am writing in my current draft book on nineteenth century cats, the Martin’s Act of 1822 was indeed positive , but the acts taken by locals, like today, were those undertaken by ordinary people who supported cats – and personally defended them!

In the Guardian on 21st October an article was entitled “London has more statues of animals than of named women” and it wrote critically that “The number of sculptures that feature animals, almost 100, is double that of named women.” While the material emerged from the London mayor’s office it apparently argued about the need “to champion diversity in the capital’s public spaces” which might be seen as displaying more statues or removing existing sculptures, particularly of animals.

Nowhere does the article state or recognise that many animal statues in London are either made by women sculptors or represent women alongside animals.

Thus the memorial in St John’s Wood churchyard in 1937 included a fox,stag, squirrel. horse, cat, dog and heron together with a bird bat and dedication to Alice Drakoules, treasurer of the Humanitarian League,and an early supporter of the League for the Prohibition of Cruel Sports.

Further the statue in Regent’s Park entitled “Protecting the Defenceless” is not only of a shepherdess and a lamb but records the work of the novelist Gertrude Colmore (and Harold Baillie-Weaver) founders of the National Council for Animals’ Welfare.

C.L.Hartwell ‘s statue with shepherdess and lamb dedicated to Gertrude Colmore (and Harold Baillie Weaver) in Regent’s Park

Similarly the restored bird bath on the Chelsea Embankment near Cheyne Walk was not solely given to birds but to commemorate the work of Margaret Damer Dawson within the Women’s Police Service in the First World War.She was also active in the Animal Defence and Anti-Vivisection Society.

Sam, the cat.is often ignored in Queen Square, but it is not just Sam being remembered but Patricia Penn who lived with him nearby.

These are not the only animals recording people – including women – but there are, of course, many animals sculpted by women. These include: Humphrey by Carole Solway, sitting in Old Gloucester Street; Diane Gorvin’s statue, including a cat, near Dr Salter and his daughter in Bermondsey called Dr Salter’s Dream and stolen some years ago; or the new old brown dog statue, replacing the destroyed one of years before in Battersea and this time paid by the old GLC and undertaken by Nicola Hicks in Battersea Park.

Let’s hope these statues are not destroyed as the result of an ambiguous statement and article. I did not search over days for this information but looked again at some of the earlier articles I wrote on these issues. If you cannot access them and want to read about them please email me.

Traces and representations: animal pasts in London’s present, The London Journal (vol 36: 1) March 2011, 54-71

‘The newly restored bird bath memorial near the Thomas Carlyle statue on Chelsea Embankment’ The Chelsea Society Report 2014, pp.66 -69

An exploration of the sculptures of Greyfriars Bobby, Edinburgh, Scotland and the brown dog in Battersea, South London, England, Society and Animals Journal of Human- Animal Studies vol 11: 4, 2003, pp. 353 -373.

See my Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entries on Alice Drakoules https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/50748 and Gertrude Colmore https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/55694

After sending an article Making Public History: Statues and Memorials last year to the Public History Review it has finally been published and is free online. https://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/phrjIt refers both to particular anti-racist and anti-slavery statues as well as progressive publications and action in schools. This includes the work of Martin Spafford, and others, who issued textbooks of Migration, Empire and the Historic Environment arising from changes agreed in the GCSE history curriculum from 2016 with the first exams in 2018.

As previously noted on this website, those interested in public history have recently pursued activities commemorating, say, a drowned black South African from a nearby southeastern channel (with remembrance in Hastings) or analysing the commemoration of African and Caribbean troops, also from the First World War, in London.

Currently out is North West Labour History Journal no 45, 2020-21, which contains former anti-slavery as well as contemporary articles. http://www.nwlh.org.uk/?q=Issue_45 Mine includes Public history and the past : slavery memorials in Lancaster, previously published there in journal no 32, 2007 and slightly amended, noting that re-readings of contested pasts have existed for many years…

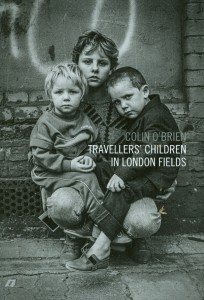

Our new paperback, by Philip Howell and me, is just out. It includes 23 articles, 30 visual images and the excellent cover photograph of Elephants Footprints, of the animal photographer, Nick Brandt..It questions to what extent animals are involved as agents in social processes, and explores the connection between artistic practice and quasi- historical features.It is not simply about the need for humans to defend animals but about the very existence of animals themselves that often been overlooked.

The hardback was selling – or not – at the sum of £188 – even being sold in Abe Books for over £200 even in Britain! I’m pleased to say that no new paperback is on sale there.

Instead in a range of suppliers the sum is within the £30 (Also available even cheaper in ebooks)

I realise that we cannot browse nowadays through books physically in libraries but they can be ordered and then available for collection to take home – even under tier 4.(At least it happens in East Sussex!) If you have online access this too can be purchased by the library as a kindle ebook.

Several reviews have supported and liked the book including:

“Kean and Howell have put together an extraordinary collection which will be a classic text not only for animal-human history in particular, but for human animal studies in general… as they are in this substantial, edifying Companion.” Wendy Woodward Animal Studies Journal 9:1, 2020.

“As a wide-ranging survey of where animal–human history has been, what it is now, and which tools and approaches can be used to expand its reach in the future, the Routledge Companion to Animal–Human History is itself a statement of the coming of age of the field. “ Nancy Cushing, Anthrozoos 33:3, 2020

“This self-conscious aim to offer essays that might introduce newcomers to the field makes this collection a truly important contribution to the fast-expanding field.… this collection shows in many fascinating ways just how we are going about attempting to address them” “ Erica Fudge, Society and Animals 27, 2019.

“… the Companion showcases not only animal-human history’s immense scope, but also the lively contradictions that abound within it. ..the political decision to include animals more explicitly in our historical writing and research is to be celebrated,. Ben Garlick, Journal of Historical Geography.66, 2019.

One of the many images in the book includes that of The Pikeman’s Dog Memorial by Charles Smith & Joan Walsh-Smith at Ballarat, near Melbourne. As noted earlier in this website the dog was there with the diggers in the C19th but has only just being acknowledged and memorialised in the C21st.

PLEASE CLICK ON THE IMAGES WHICH CAN THEN BE CLEARLY SEEN

During the current pandemic, attention is being paid to apparently “normal” interests in families at Christmas time. This doesn’t completely grip with my own thinking as an adult. But I recently recalled earlier times as a child. These came from two earlier sorts of writing from both my last year at Millfields primary school in Clapton and then the first year with my English exercise book at John Howard School. They were written around the age of 11 and seemed to note different things in a somewhat Christmas setting. The first was a poem about a family trip to the Royal Festival Hall and The Nutcracker Suite.

It seem I was keenly interested in dance but then I focussed on trying to get to a weekly ballet class which finally I achieved, perhaps as a reward for passing the 11+? Yet after three years even I realised I wasn’t up to it and gave up.Not until decades later, when I took early retirement, I finally returned to do ballet classes . So some generally positive times have now passed happily- until c-v – at the CIty Lit near Covent Garden, in beginners’ ballet classes of the wonderful Martin Wimpress. I even moved up into intermediate ballet class but the pandemic has been impossible. Let’s hope this excellent teaching can continue in the college.

The second writing is a short piece from my first year at the local John Howard girls’ grammar school with the teacher’s comment.

Perhaps I had thought this might relate to some people’s Xmas focus on buying turkeys and chickens? At first I wasn’t a vegetarian , only reaching it decades later and a vegan later still. I guessed I was critical of the position of dead animals and even noted their poor treatment then ; though it seems that the teacher read it in another way !

Instead of such writing no doubt an online ballet and vegan nut roast may be something positive in 2020….

Sometimes it’s odd looking at statues in different ways. I tend to see them in open spaces or museums and often take photographs. Some years ago I did this in Gundagai, New South Wales,Australia. The statue was called ‘Dog on the Tucker Box’. it was not built about a real animal. It consisted of a small bronze statue of a solitary dog fixed to a stone base erected over a wishing pool. At the bottom was mounted a plaque with verse composed, and a plaque recording its unveiling in: 1932. Even though the dog never existed, it was well-known from at least the nineteenth century, through stories and poems,as :

But Nobby strained and broke his yoke,

And poked out the leader’s eye;

And the dog sat in the tucker box

Five miles from Gundagai.”

Although a recent article described the dog as ‘one of Australia’s most successful purpose-built tourist attractions’ it forgot to note the local commemorations to Yarri (and Jackey Jackey) . These Aboriginal men rescued c. forty nine white people from the massively swollen and dangerous waters of the Murrumbidgee River. In recent years a concrete bridge was named after him and a new monument was erected in North Gundagai cemetery since this had been ‘in the memory of Gundagai people for generations’

I’ve never previously seen a visual image of even the Dog on the Tucker Box in Britain until a few weeks ago. In Marks and Spencer sat bottles of white wine, pinot grigio and chardonnay, apparently from Paul Sapin, a French firm, but originally from Australia.As an Australian public historian advised me this did not appear on bottles sold over there…

How this is a focus on Gundagai seems beyond me since few Australians -and even fewer Brit tourists – went to the site even several years ago. Perhaps it’s just part of the pandemic situation in which we see things in rather different ways…

In 2012 on this website I drew attention to Alan Rice’s book Creating Memorials, Building Identities: The Politics of Memory in the Black Atlantic http://hildakean.com/?p=1300 and related this to the memorial I had visited in Edinburgh’s Old Calton burial ground noting,”The images are of an interesting memorial by George Bissell in Old Calton burial ground, Edinburgh unveiled in 1893. Ostensibly it is in memory of 5 named Scottish-American soldiers who had fought in the American Civil War. However, on top is a statue of Abraham Lincoln and at the bottom a bronze life-sized figure of a slave promoting a more specific anti-slavery message…”

Recently it has been stated that this statue was ‘the only monument to the American Civil War outside the U.S. A statue of Abraham Lincoln standing over a freed slave’. Yet I have not recently seen a description of this past monument with its anti-slavery depiction.

Again in the past, even in Hastings in East Sussex, attention was drawn, not in 1893, but 2016 to the presence of one member of the South African Native Labour Corps on the SS Mendi troop ship. Corporal Jabez Ngozo died in the sea and was buried locally in 1917 decades ago in Hastings cemetery off the Ridge. Surrounded by the military dead of the First World War from all corners of the world, the only South African Native Labour Corps soldier was found in Hastings and buried here and likely to be the only man of colour in that plot. Nearly 617 fallen African black men who died on the SS Mendi ship have been commemorated in Southampton where their bodies were found nearby . The Mendi had sunk in the Solent on her final leg of the journey to Le Havre from Cape Town, via Nigeria.The Mendi sank on 21st February 2017. It sank as a result of a large cargo ship, colliding with her on a foggy night. The court of enquiry recorded it as an accident but the Master of the cargo ship had his licence suspended for a year for not stopping to assist the casualties.

Ngozo’s grave had not been particularly emphasised or described until local historians, Dee Daly, Susannah Farley- Green and former Labour council mayor Mayor Bruce Dowling and Cllr Terri Dowling explained. The grave and the story of the Mendi was well known but by an accident of fate Cpl Ngozo’s grave had not been connected to the tragedy by South African historians. While visiting the South African National War Memorial in France at Delville Wood they directed attention to the curator Thapedi Masanabo who immediately alerted his Ambassador in Paris who ensured that this lost soldier of the South African Labour Corps took his rightful place on the memorial which was being planned back in South Africa. As Dee Daly explains: “Two of our party that year were Hastings Borough Councillors and one of these was the Borough Mayor for 2015; their ability to highlight the importance of Corporal Ngozo in the local press brought an understanding of the experience of the people of colour of the Great War to a wider population; most particularly the appalling and needless deaths of those who perished following the loss of the SS Mendi.”

In due course flags of the current South Africa appeared on Ngozo’s grave in Hastings. And Ngozo has now been included in the South African Grave commemoration in France and in South Africa.

Bruce Dowling and Terri Dowing, Hastings councillors, and Thapedi Masanabo, curator, at the South African National War Memorial

In Hastings, attention was clearly drawn to a burial over 100 years ago of a particular unknown man, Jabez Ngozo, and accounts then made of his background. In Edinburgh too notice was made of earlier Scottish soldiers in the American civil war alongside the presence of a statue of a black slave and still surviving two centuries later.

Some memorials have indeed been acknowledged, albeit not widely written about, in materials that are publicised centuries later than specific events. It is not the case that necessarily no history was present there or known about centuries -or even decades- ago. Rather, knowledge from the past needs to be given to the memories and materials and even statues that did – and do – exist. (As noted in “Statues and Histories from Past Decades” http://hildakean.com/?p=3378)

Stories of cats – and often their visual images- occur in archives of the nineteenth century, particularly London. .In the Bank of England in the City of London around fifty cats were kept – to act as mousers- and a weekly sum was regularly allowed for their support. On one occasion in 1819 a principal clerk in one of the offices was bitten a couple of days before by one of the cats. Consequently “suspicion having subsequently arisen that the animal was mad” resulted in all the cats being destroyed (with the clerk having the bite excised).

Images occur of cats for sale in a range of shops including those also selling birds and dogs, as shown in The English Magazine of 1886.

In the early accounts of London factories in the 1840s there are depictions of cats , including,just sitting in a sugar refinery.

Although accounts of animals, including cats, appeared in a range of radical accounts, such as those of the Chartists,or the later Justice press of the SDF, I have rarely come across progressive accounts during the twentieth century in factories. However in the Past Tense – which often includes materials about politics in London – I have come across “A series of guerilla strikes begin at the ENV Engineering Works, Willesden”. “E.N.V. was an early manufacturer of aircraft engines… ENV’s works in Willesden became a hotbed of rank and file union activity, which peaked in a series of strikes in 1966” closing in 1967.

Reference is made to the work of Joyce Rosser and Colin Barker who described activists stating “The obvious candidate for the post of convenor among the remaining stewards was the deputy convenor, Sid Wise, an ex-member of the Trotskyist Revolutionary Communist Party, and for a short time, with Gerry Healy, a member of the Socialist Outlook group. The Communist Party stewards, however, not wanting a Trotskyist convenor, proposed in his place Harry Ford.One of his jobs was the setting of traps round the factory to catch the numerous cats that infested the place, and workers went around releasing the cats. Harry Ford complained of ‘lack of cooperation.’ ”

I do not recall this being accounted for in many trade union activities. It seems rather than being killed – as happened at the Bank of England – the cats were being freely released into the factory – despite the apparent position of the leading CP convenor!

I’ve been looking at cats’ existence in the 1800s – no doubt the 1900s now also need to be explored…

Much has been raised in recent days about statues, particularly in Bristol and London. Yet many of these arguments are not new topics but have been written about broadly and critical of dismissive approaches for many years.

Bristol. Madge Dresser, Honorary Professor at the University of the West of England in Bristol, has written both about the 1963 “colour bar dispute” since 1986 and books against slavery in Bristol and nearby country houses for many years. As she states on twitter “Efforts to rebrand Colston statue plaque to tell the whole truth about the man-have been stymied for years.” Then in Bristol Sally J Morgan, now Distinguished Professor of Fine Arts at Massey University Wellington, wrote particularly about the Edward Colston and also John Cabot statues in an article : “Memory and the merchants” over 20 years ago in 1998. She wrote, “In the English city of Bristol similar attempts at confiscation have occurred and can be traced to the city’s controlling mercantile class as represented by The Society of Merchant Venturers, established in the 16th century and still going strong, who have contrived to forget almost as much as they demand we remember…”

London. Madge Dresser also wrote 13 years ago “Set in Stone? Statues and Slavery in London”. This included the display in London’s Guildhall of the former mayor, William Beckford: “The evidence linking William Beckford (1709–70) to slavery is widely available and overwhelming. Beckford, twice Lord Mayor, was the free- spending son of a wealthy sugar planter and owed much of his position to his ownership of some 3,000 Africans enslaved on his numerous Jamaican plantations.” Similarly, John Siblon in his ““Monument Mania”? Public Space and the Black and Asian Presence in the London Landscape’ of 2009/12 included differently the black sailor with a musket at the Battle of Trafalgar at the bottom of Nelson’s Column. Clearly visible -but rarely noticed even in demonstrations in Trafalgar Square – Siblon argued for the need for further state representation in London. He later analysed the nature of the memory of “African and Caribbean Troops from Former British Colonies in London’s Imperial Spaces” . He stated 4 years ago, “During the First World War efforts were made to publicly acknowledge the service of Africans and Caribbeans but after the war the evidence points to their deliberate omission in the state-sponsored cultural memory of the war.” Elsewhere in London I wrote about “The Gilt of Cain,” a site-specific work in Fen Court, London, near the Lloyds building which combined material of the Scottish sculptor Michael Visocchi with the poetry of Lemn Sissay. Visually, the sculpture consists of variously sized cylindrical columns, resembling sugarcane – or possibly human figures. Alongside this is a structure representing a pulpit – or an auctioneer’s platform.The work was initiated by Black British Heritage, chaired by Ken Martindale, who was involved in community politics, including the Notting Hill Carnival for many years.

Lancaster. Professor Alan Rice ,advisor to the Slave Trade Arts Memorial Project (STAMP) for many years ago, has analysed and publicised “Captured Africans,” sculpted by Kevin Dalton-Johnson using stone, steel, and acrylic and located outside the former customs house on St. George’s Quay in Lancaster, once the fourth largest slave port in England.

Works to read about issues on black lives still exist and have existed for decades.In some ways reading about already analysed work can actually assist many in the current situation who seem not aware of historical and critical material. Some of the writers were postgraduate students in Public History at Ruskin College where a range of conferences and discussions took place. This course no longer exists but many relevant reading lists should still be read today including:

Peter Fryer Staying Power. The History of Black People in Britain Pluto Press,1984.

Madge Dresser Slavery Obscured: The Social History of the Slave Trade in an English Provincial Port. 2001

Black and white on the buses : the 1963 colour bar dispute in Bristol Bristol : Bristol Broadsides, c1986.

Set in Stone? Statues and Slavery in London History Workshop Journal, Volume 64, Issue 1, Autumn 2007, Pages 162–199,

Sally Morgan Memory and the merchants: Commemoration and civic identity, International Journal of Heritage Studies, 4:2, 1998.

John Siblon Negotiating Hierarchy and Memory: African and Caribbean Troops from Former British Colonies in London’s Imperial Spaces, The London Journal, 41:3, 2016,299-312

“Monument Mania”? Public Space and the Black and Asian Presence in the London Landscape in People and their Pasts ed Ashton & Kean 2009 / 2012, pp.146 -162

Hilda Kean Where is Public History? (re Lancaster and London) A Companion to Public History ed David Dean, p.33-542018

Alan Rice, Creating Memorials, Building Identities. The Politics of Memory in the Black Atlantic, 2010.

I was asked to write an article five years ago on animal statues after speaking at a Geography (!) conference alongside many other speakers on animal papers. My article called “Remembering animals of the past and creating new sculptures of animal relationships with humans” has just come out in a book called Creating Heritage edited by people at the Geography conference who were very into heritage though, it seems, not particularly interested in animals. The book is published within a series formally described as “of an interdisciplinary social science forum for original,innovative and cutting edge research about… cultural heritage-based tourism.”

As you probably guess from bits on my website my article is nothing about this . The article focuses particularly on three animal statues I have previously discussed on this website, drawing on different times in Sydney, Australia and Wellington, New Zealand. The writing includes Trim situated behind Matthew Flinders in Sydney, Paddy the Wanderer outside the local museum near the former docks in Wellington,having lived with taxi-drivers, waterfront workers and ordinary sailors. Mrs Chippy, the cat, is sitting on the earlier grave of Harry McNeish, her human companion, in the Karori cemetery outside Wellington although she had been killed by Ernest Shackleton on the Endurance boat in 1915.

Mrs. Chippy’s statue by Chris Elliot. On Harry McNeish’s grave in Karoro cemetery, Wellington, New Zealand

On my website are various stories of these particular animals- and many others – to access: just click on the search up the top on the right using their names or cats /dogs etc.

In different ways I have considered how the animals themselves brought attention to humans who existed but were not necessarily praised in earlier time. Mrs Chippy gave commemoration to Harry McNeish who died in 1930, although she was only placed on his tomb in the cemetery in 2004. And Trim, the cat, was remembered only in 1996 behind the statue of the explorer Matthew Flinders who died in 1814 and whose own statue was erected in Sydney long ago in 1925 – without Trim being commemorated with him.

Routledge – like most of its recent books – is trying to get readers to spend £115 on just one book – even without a front cover visual photograph /image. (A bit like the Routledge Companion to Animal-Human History- edited by Philip Howell and me – that is now costed at £190 even despite the wonderful image of Nick Brandt on the front cover). Needless to say, even at Abe books Creating Heritage goes from £96 to £135 and Animal-Human History from £121 to £284, yes £284)

Just have a look at the nice animal statues here!

(Don’t worry I did refer to Flinders and Trim now also in London’s Euston station… which looks rather different to this cat!)

Historian Raphael Samuel died nearly 23 years ago (on December 9th 1996). We had worked together as historians at Ruskin College, where I was employed from 1993. I knew he was very ill and based in his Spitalfields home in London.

Oddly I recall that one day I was working in the then wonderful, dark , British Library in the British Museum. The place was not just a wonderful site for me but where I would have often seen Raphael rummaging away. I had not looked at a newspaper until I left early in the evening to then, distressingly, see an obituary of Raphael’s death – on just the previous day – already included on a large page.

Although I have often recalled him I had probably forgotten about when this sudden memory took place and now find it striking that his death occurred – before my own age now. Now I have only just recalled speaking at his memorial celebration in Conway Hall and also arguing for the re-naming of a Hall in the then Ruskin College with an engraved wooden memorial in his name, (When Raphael Samuel Hall was demolished – alongside Ruskin College itself – the wooden plaque went to the Bishopsgate Institute where it is proudly displayed – just some yards from Raphael and Alison’s former home.)

But I have started to recall this not through talking to anyone in particular but through reading A Radical Romance just officially launched and written by his wife, Alison Light. That this was only finally written and published now is striking. It is a wonderful book first involving Alison’s autobiographical experience revealing details of being a particular teenage young woman. (I could never manage to write about my life in that way.) Issues around Raphael’s life and his focus on writing comes to life but primarily it is a text written about the lives of Alison and Raphael together (irrespective of the rants of historical hysteria in certain times and places…)

While the book is so well written and engaging it has also reminded me of many things I had forgotten about working with Raphael so many years ago. I therefore include below, an image of a day out around Ironbridge where we went with some of our then History students at the end of year in 1994.

I ended up in tears finishing the book on a train into London, not because it was simply distressing but rather because it clearly captured so engagingly the explicit time in which Alison and Raphael lived. This is one of the most wonderful books I have read and would thoroughly engage people, particularly those who knew Raphael in various ways, as well as people thinking about their own memories and of lives of friends now ended. (A Radical Romance. A Memoir of Love,Grief and Consolation, (Fig Tree, an imprint of Penguin Books. Only just out but already cheaper than the hardback in Abe Books!)

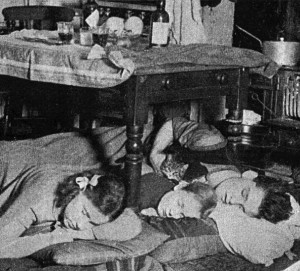

80 years ago – start of the Second World War and thousands of deaths of pet animals…

At the start of the war many dogs (and cats) were protected by the Animal Defence Society in London to stay in their Ferne premises during the war

During the Munich crisis in 1938 a year before the Second World War newspapers described blind panic- and certain people fleeing quickly from London. Some rushed with their pets to animal charities where some pets were killed at the RSPCA ,Battersea Dogs Home and The Our Dumb Friends League, (now the Blue Cross). The National Canine Defence League (The Dogs Trust) refused to do this. Animal charities realised what might happen in the future…

In the many months before September 1939 the RSPCA and vets advised the Home Office on “questions in connection with the protection of domestic and captive animals” . By August 1939 an umbrella organization was created in the form of the National Air Raid Precautions Animals’ Committee (NARPAC),and established through the ARP department of the Home Office by the Lord Privy Seal.It said:

“Those who are staying at home should not have their animals destroyed.Animals are in no greater danger than human beings, and the NARPAC plans . . . will ensure that if your animal is hurt it will be quickly treated, or put out of its pain if it is too badly hurt to be cured. Another very strong point against destroying animals is that they play an extremely important part in keeping down rats and mice in our cities.”

The government had not issued a diktat or emergency measures requiring animals to be killed. But many people did this , particularly in London, in the first week of war in September 1939. The press covered the mass slaughter of some 400,000 dogs and cats in London alone. This figure was later corroborated both by the RSPCA and Brigadier Clabby, of the Royal Army Veterinary Corps.

This slaughter of 400,000 animals was more than six times the number of civilian deaths on the Home Front caused by enemy bombing during the entire war in the whole country. Importantly no bombs had actually fallen that September 1939 and none would fall on London—or Britain—until April 1940.

September 1939 is now being recalled as a memorable 80 year old event. It should also be remembered for many lost lives of domestic animals. As Richard Overy recalled on The Great Cat and Dog Massacre cover “ this process offer[ed] a profound view of the way animals and humans interact.”

(Photographic images in my book show cats and dogs animals being protected – not destroyed)

A new unusual photographic book is well worth reading. This is Allowed to Grow Old. Portraits of Elderly Animals From Farm Sanctuaries taken by Isa Leshko.

Isa first met Petey a 34 year old Appaloosa horse and stated that when she reviewed the negatives from her afternoon with Petey, she realized she had stumbled across a way to examine her own grief and fear stemming from her old mother’s illness. She would then find other elderly animals to photograph.She photographed many animals ending their days in safe sanctuaries.

They include Babs , a donkey, who was a former rodeo animal used for roping practice and covered in rope burns. She suffered from many diseases that were then helped in Pasado’s Safe Haven in Sultan, Washington.

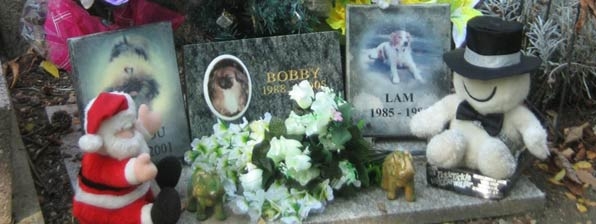

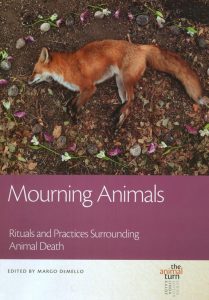

I have been interested previously in works dealing with the death and mourning of animals [having contributed to Animal Death – on pet cemeteries – or Mourning Animals – on dead animals in wartime-]. However the powerful images of elderly animals, often photographed by Isa as she laid next to them on the ground, is unusual. I have often looked at the older animals now living and surviving in the Hillside Animal Sanctuary in Norfolk being rescued from cruel circumstances but have yet to see such photographic images recorded in this way in Britain.

I would recommend this large book published at £30 by the University of Chicago Press and already having received much support from writers such as Carol J.Adams, Marc Bekoff, Steve Wise ,J.M.Coetzee and Peter Singer.

The wreck site of the ‘Amsterdam’ ship of 1749 lies outside Hastings near Bulverhythe on the walking route to Bexhill.

Nearby are elements of a prehistoric forest of 2000 BC and outcrops of cretaceous rocks of 135 million years old.

Normally it is difficult to see any of this even from the path adjacent to the beach because of the high water. But low spring tides have revealed these perspectives alongside contributions from volunteers at the Hastings Shipwreck museum.

Due to entering the English Channel under a severe gale the ‘Amsterdam’ ship struck the seabed so hard that her rudder was torn off. The wreck together with goods were buried within the sand.When some workers digged into the wreck in the late 1960s they found bronze cannons, clay pipes, personal possessions etc. As a result -unsurprisingly- archaeologists were horrified at the damage and sought its protection as an historic site.

You can walk over the Bridge Way from the Bexhill Road (that goes from Hastings to Bexhill) and view the area but will be unlikely to few the wrecked ship or the wooden fossils nearby unless there is a low tide. Though living in Hastings now for a few years I’ve only just managed to see it properly for the first time. I would recommend a visit.

(No stories of the existence of cats…)

Recently I noted the presence of several animals – including cats – in London exhibitions and wondered about the curators’ choices .

I was not over impressed by a recent visit to a Ruskin bi-centennial exhibition, The Power of Seeing, at Two Temple Place on the Thames Embankment. Needless to say no comment was made on John Ruskin’s agreement to offer his name to the working class adult student College that would develop in Walton Street Oxford shortly after his death. (Ruskin college is no longer in that Oxford locality, next to Worcester College, being destroyed just a few years ago in this C21st.)

The exhibition displays images of birds including parrots, cockatoos,duck and an interesting peacock head by J M.W.Turner.But of particular interest was a nineteenth century head of a cat engraved by Arthur Burgess , in brush and ink over charcoal on “wove paper” from the Ashmolean museum in Oxford. Burgess was a wood engraver who asked Ruskin for illustration work. The enlarged drawing is from Durer’s Adam and Eve painting dating from 1504 including cat, a rat, hare or rabbit ,cow, goat, bird – and snake.

I have now dipped into my Durer book for 10/- given to me by a friend in December 1970 while I was studying Medieval Latin at the University of York. The book recalls the Adam and Eve images from Vienna and Pierpont Morgan library in New York . I have no memory of seeing the cat from that particular time but am interested in the engraving of Burgess now displayed. Clearly it was of interest in the nineteenth century but now also seems popular in a small new exhibition .

I am speaking this week at the Wigmore library in Gillingham, on what happened to animals, particularly in London, during the 1939 -45 war (see the events notice). Positive individual animal stories that have passed down in families will be raised.

While I will probably pay attention to Winston Churchill’s personal relationship with cats, including the black Nelson in Downing Street and his ginger in Chartwell, I will also refer to another Winston Churchill. This one was a Siamese cat born on Jersey in 1941 who was fed on limpets and managed to evade the Nazi troops since he scarcely left the house. Another family cat was called Hitler, because of a black patch under his nose. This cat was also taught ” to raise its right paw in some parody of a Hitler salute when it was given food”…

I intend to pass around some visual images of the time, though I don’t imagine circulating the Spratt’s advert for a dog gas mask (above). Though photographic images of dogs wearing masks do exist, unsurprisingly dog gas masks rarely seem to form part of a written or clearly passed down family story!

Cats – as well as as dogs – started to be included in the Battersea Dogs’ Home – as noted in The Strand Magazine of the 1890s.

A couple of years ago a one-off conference was held in Paris with mostly english presentations under the title of “Becoming animal with the Victorians” apparently explaining that “creatures comforted human beings in the nineteenth-century, and became them, not only in the sense of enhancing and suiting them but also by virtue of that human-animal ability to grow together in trust and tenderness.”

I gave a conference paper – though it was certainly not primarily based on the ability of humans to grow together with animals in trust and tenderness. Rather, I had been thinking instead about the way cats were treated at the time and in particular the way there were records of cats being skinned often stated , as The Times reported, in “ sausage-making, cat-skinning, knackers’ yards,bone-boilers”. I was not as convinced as some writers who have suggested that improvements had been fully made and that humans had led the way positively.