Whose archive? Whose history? The Women’s Library and Ruskin College, Oxford

I have recently been involved in the campaign to save the Women’s Library currently housed in a purpose built library and exhibition space in London’s East End. As I have written elsewhere, the library was initiated by the London Society for Women’s Service with two objects:‘to provide a good working library on social, political and economic subjects for its members and to preserve the history of the women’s movement in which the members themselves had played an honourable part’. Former librarian, David Doughan, described it as ‘ the largest and most comprehensive source of information on women in the UK, if not the world.’ The decision of the governors of London Metropolitan University to transfer the collection and, under TUPE, the staff to the LSE has been seen by some as positive. Yet while it is clearly good that the collection is not being trashed, the fact that it is leaving its purpose – designed building achieved through a Heritage Lottery Funded bid is not positive. Rather than being a walk-in facility in one of the poorest boroughs in Britain its transfer to an elite university that has so far declined to also take the exhibition space is to be lamented. The whole character of the place will potentially change from a site of activism connecting tangibly with the world outside to one of introspection practised by academics.

However, this is not the only progressive archive under threat. Ruskin College, Oxford, the labour movement institution founded in Oxford in 1899, has recently sold its building in central Oxford to Exeter College and has moved to the outskirts of the city to Headington. Fortunately one of its collections relating to the History Workshop Movement has already transferred to the Bishopsgate Institute in London. The Bishopsgate volunteered to take any material that Ruskin did not want. Reject material includes the MA dissertations undertaken in the last 15 years by students on the pioneering Public History course but other, older material has a much less secure future.

Unique material has already been trashed. This includes records of some of the trade union students who attended Ruskin in its first decades. These were activists, sponsored by their unions, who usually went back into the trade union and labour movement as leaders. Such archival matter is like gold dust to labour and social historians – and, of course, to former students’ descendants – enabling a better understanding of the political and cultural life of working class people in the twentieth century.

However, the college principal, Audrey Mullender, has decided that such material should be destroyed. Most of the files, she says, are ‘extremely thin and boring’ and do not provide ‘a complete record’. This indicates a complete lack of understanding about the nature of archives – and why historians find them fascinating.What is extremely boring to one individual is often fascinating to a historian re-visiting the material in decades to come. In New Zealand, for example, one short sighted official destroyed nineteenth century census records thinking they would be of no interest whereas, of course, these are items of fascination to family historians. Even within state records one never receives full records – the 1861 census, for example, has huge gaps. Archives never contain ‘complete’ records. Choices are always made by depositers and archivists. There is no ‘objective’ position. This is one of the reasons that historians find archives tantalising and absorbing.

There is a fundamental misunderstanding too about the status of personal material such as that contained in former student applications. Routinely readers in archives are forbidden from accessing personal archives for some period of time, currently usually 70 years. Archives have the facilities and rationale for ensuring that records are preserved: colleges do not automatically have the space especially when a new supposedly purpose built library has less storage space than the library it is replacing… Audrey Mullender has been informed that an institution donating to an archive can have control over access and that a receiving institution can have the knowledge that in the future such materials can be accessed.

To date some unique and rare material has been taken away from the old college and has already been specifically destroyed. Some apparently still remains – awaiting the same fate.

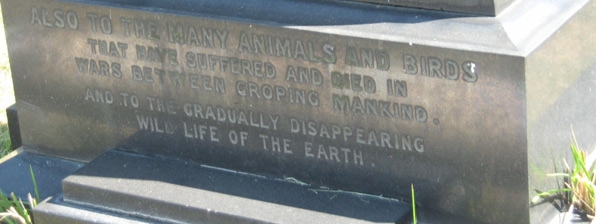

Women’s and labour history are being pushed back into the margins from which they emerged after a long fight in the 1960s and 1970s.One is reminded – yet again – of the prescient writing of Walter Benjamin , namely, that ‘every image of the past that is not recognized by the present as one of its own concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably.’ He also writes of the role of the historian to fan the spark of hope in the past and that such a historian is one who is firmly convinced that even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if the enemy wins…

Sign the petition on Care2 site now to stop further archive destruction at Ruskin College, Oxford.

A longer article discussing the destruction of the Ruskin archive is now available at History Workshop Online

What a dreadful irony that in the period of the death of Eric Hobsbawn institutions which should be seen as bastions of the cultural and political legacy of radicalism and protest are attacked from without and within. It is a further tragedy that it was Hobsbawm and his contemporaries who helped push this very history into the forefront of public understanding and consciousness. Ian Manborde.

Sadly the people trying to save these precious resources are not linked up with some of the people and organisations who might be able to help. There are social enterprises and other new ways of doing things that could rescue these institutions. In the case of the Women’s Library this means persuading London Met and LSE to delay signing contracts – and that requires a massive campaign ….. but those that have been fighting this over the summer are now exhausted – what to do???

What has happened to the Labour History and Radical Social Movements Archive at Ruskin College over the last few years is ignorant vandalism. It amounts to a failure of a profound duty of care and responsibility. Trade Unionists, socialists, radicals, ex-students (many of them) engaged in political struggle, contributed texts to this archive over generations. This is the memory of the Labour Movement in this country sold for 5p and 10p or thrown away with the rubbish. What can you expect from a Principal who dismissed Ruskin’s radical past at a public meeting a few years ago as ‘all so last century’. Tell that to people on strike today.

I cannot fathom why the Ruskin College records are being destroyed. They were invaluable to me when I was writing The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes. I have signed the petition, but if there is anything more I can do, please contact me.

Although thousands of student records have already been destroyed – as Ruskin principal has confirmed in a story in the Daily Telegraph – some still remain.Let’s hope letters to the press and governors will be able to save the historic student records that still remain.

This story is typical of many more, where on the one hand archives associated with social movements are being thoughtlessly destroyed and on the other hand there are major cost in creating good archives and storing them. I found this in trying to preserve the archives of Word University Service,WUS. WUS had for almost a century built up invaluable archives showing on its own work and particularly it work of assisting refugee students from Hungary,Czechoslovakia,Chile, Uganda , Rhodesia/Zimbabwe among others. Much of this was lost as the organisation went into liquidation a few years ago. Fortunately some was saved and some records are held at the Modern Record Centre at Warwick University.

A new campaign ( Campaign for Voluntary Sector Archives) has been created and will be launched at the House of Lords on Monday 15 October. The preservation of voluntary sector archives is an area where we believe that bodies like the Charity Commissioners have a crucial role to play.