Knowing and not knowing what will be historical

Some of the former History students of 1993-4 whose records have been shredded with the late Raphael Samuel whose records are safe in the Bishopsgate Institute

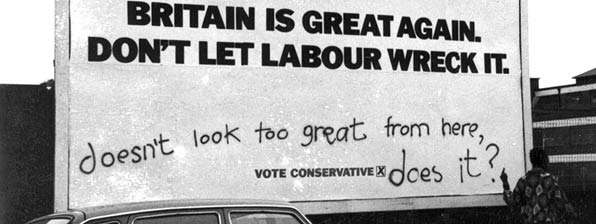

Apart from the fairly obvious divides of philistinism and vandalism vs. culture and conservation that distinguishes those who wish to save traces of the past and those – such as the management of Ruskin College – who destroy material as irrelevant, there are other very sharp contrasts in ways of seeing the world.

The petition to date – to be presented to the Ruskin college governors later this month – contains more than 7,500 signatures well above the initial target of 5,000. From the ways they define themselves and their interests the signatories are broad in scope including novelists, MPs, trade union activists, university professors, archivists, librarians, family and local historians, former students and staff and many who choose to be anonymous which in itself is somewhat telling given the nature of some of the comments…

Some refer specifically to their anger at the loss of material about the lives of their ancestors who studied at Ruskin,’My father was one of the early Ruskin graduates. He attended through a Worker’s Educational Association scholarship, after having started as an apprentice welder in the Chatham shipyards. He graduated and went on to be selected for a social work post at Toynbee Hall. WW2 intervened (he joined the RAF). I cannot conceive, as a historian myself, that such destruction is justified…’ As another argued,‘These records are irreplaceable, they show the lives of our ancestors. They give meaning to their lives and show what they went through and what became of them’. Some talk about the nature of labour and working class history,‘The records and voices of working class people matter as much today as they ever have’ says one Others encompass the archives of Ruskin within the national heritage, ‘I see little difference between archive destruction and book burning. I find it difficult to understand why this can happen in a civilized nation.’ Some relate the archives to their own lives and experiences, for example as former students at the college, ‘Bishopsgate would be the best place: as the late Raph Samuel’s archives are kept there. He taught and loved Ruskin. I was lucky to be at Ruskin 1995/96 . I can’t believe the vandalism of such important archives’. As one movingly describes, ‘My father was lucky enough to gain a scholarship to Ruskin, from the NUM after WWII. His studies there are a large part of the reason why I am not now a miner. Or at least an ex miner. These records are of international importance.’

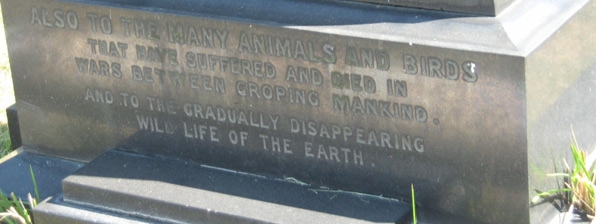

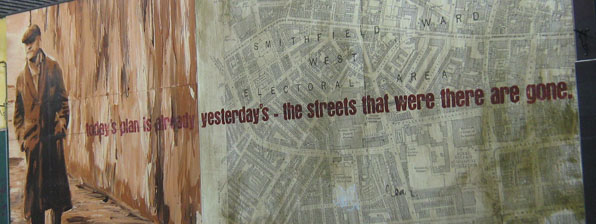

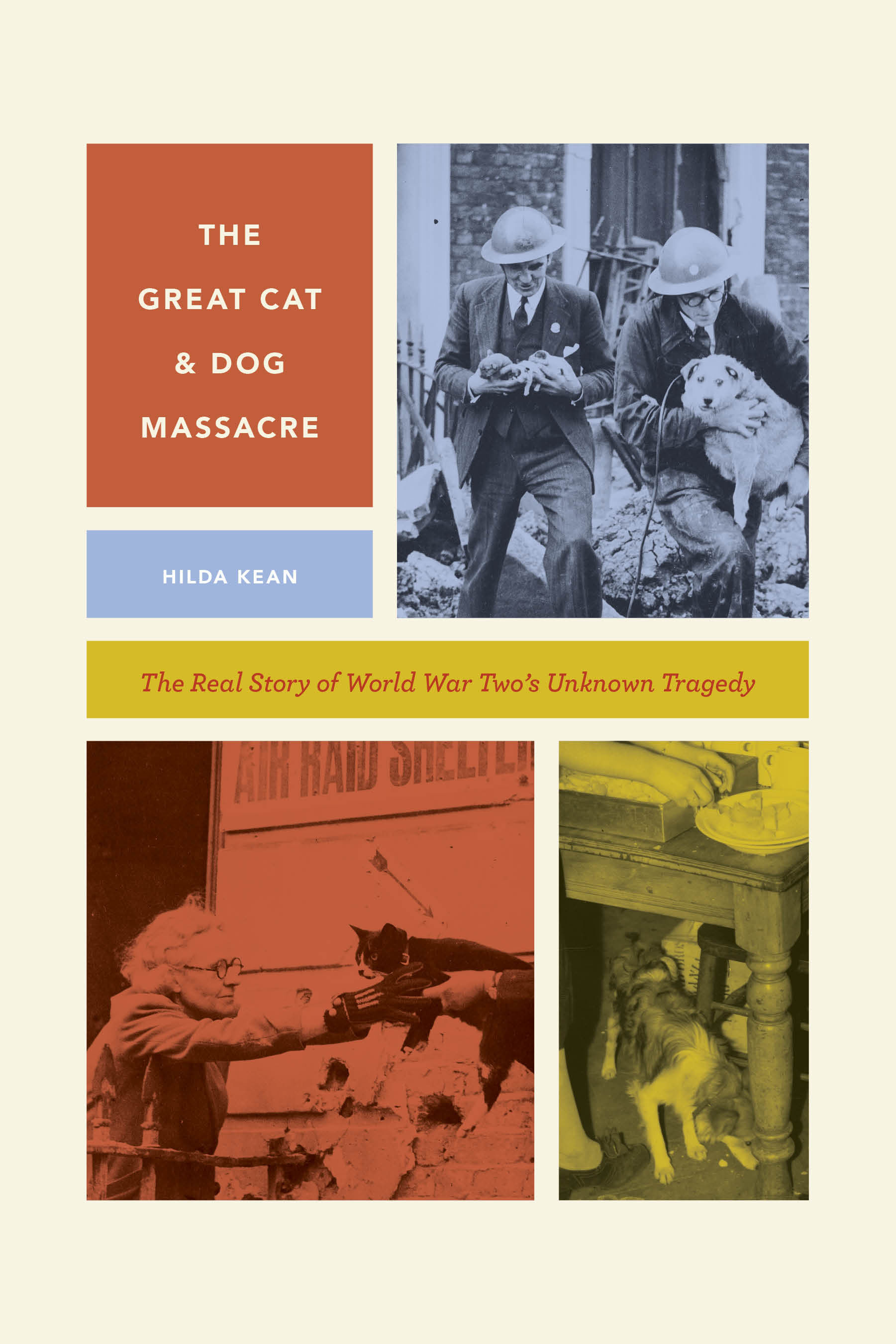

Two features are striking. The first is the international scope of responses from five continents and dozens of countries: this is not just an incident happening in a very small and unimportant college in a small, albeit iconic, city. The second is the nature of historical awareness. Although some are very keen to declare that the already destroyed material (and hopefully the remainder to be saved if the governors can be convinced) is of intrinsic value to historians today others are less definitive in their approach. The latter cohort realises that although the material for writing history can remain – provide it isn’t shredded and dumped in landfill, of course – how it might be used by future historians cannot be decided by the current generation of historians. For example, I am not at all sure that even labour and feminists historians of the 1960s, who were themselves pioneers in writing about new and hitherto neglected subject matter, would have foreseen the growth in interest over the past lives of non-human animals. Those of us who research the past (and present) animal-human relationship are able to do this because of material such as diaries that exist in which animals feature although they were not necessarily the only focus of that genre. This awareness of being unable to control the future but seeing the need to preserve the present and past for those who come afterwards is a different way of seeing the nature of time and the process of history-making. It is quite distinct from an approach that focuses upon a personal ‘legacy’ by seeking to control the past. As one signatory put it ‘As a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and former museum director, I find the decision to destroy these records unbelievable and quite irresponsible when an appropriate repository for them is seemingly available. I would urge the principal and governors to show some humility and recognise that they may have got this one wrong.’

Clearly the 7,500 people who are concerned about the remaining Ruskin student archives realise that the present in all its vagaries needs to be preserved for others to create the histories they need in the future. As one argues, ‘What an incredibly short-sighted act. If the destruction goes ahead future generations will wonder at how little we cared for our own history.’

Leave a Reply